SAMtools: Primer / Tutorial

by Ethan Cerami, Ph.D.

keywords: samtools, next-gen, next-generation, sequencing, bowtie, sam, bam, primer, tutorial, how-to, introduction

Revisions

- 1.0: May 30, 2013: First public release on biobits.org.

- 1.1: July 24, 2013: Updated with Disqus Comments / Feedback section.

- 1.2: December 19, 2014: Multiple updates, including:

- Updated to use samtools 1.1 and bcftools 1.2.

- Updated usage for bcftools.

About

SAMtools is a popular open-source tool used in next-generation sequence analysis. This primer provides an introduction to SAMtools, and is geared towards those new to next-generation sequence analysis. The primer is also designed to be self-contained and hands-on, meaning that you only need to install SAMtools, and no other tools, and sample data sets are provided. Terms in bold are also explained in the glossary at the end of the document.

Feedback

If you find an error in this document, or would like to send specific feedback, please send email to: cerami AT gmail.com.

Sample Data Files

You can access all sample data files for this primer from the companion github repository.

From the repository, you can:

- browse and download individual data files.

- download a complete zip file containing everything.

- clone the entire repository. If you have never used Github before, there is a comprehensive tutorial to get you started.

Introduction

Next-generation sequencing refers to new, high-throughput technologies for sequencing DNA or RNA. A typical work-flow for next-generation sequence analysis is usually composed of the following steps:

SAMtools fits in at steps 4 and 5. Most importantly, it can process aligned sequence reads, and manipulate them with ease. For example, it can convert between the two most common file formats (SAM and BAM), sort and index files (for speedy retrieval later), and extract specific genomic regions of interest. It also enables quality checking of reads, and automatic identification of genomic variants.

Installing SAMtools, bcftools

To get started, download the SAMtools source code from: www.htslib.org. Then, unzip and unpack the distribution to your preferred location –– for example, I have placed SAMtools at: ~/libraries/samtools-1.1/.

SAMtools is written in C, compiled with gcc and make, and has only two dependencies: the GNU curses library, and the ZLib compression library. If you are using a modern variant of Linux or MacOS X, you probably already have these libraries installed.

To build SAMtools, type:

make

Next, download the bcftools source code, also from: www.htslib.org. As with SAMtools, unzip and unpack to your preferred location – for example, I have placed bcftools at: ~/libraries/bcftools-1.1/.

To build bcftools, type:

make

Then, add the samtools and bcftools executables to your path. For example, I have modified my .bash_profile like so:

export PATH=/Users/ecerami/libraries/samtools-1.1:$PATH

export PATH=/Users/ecerami/libraries/bcftools-1.1:$PATH

As an optional, but recommended step, copy the man page for samtools.1 to one of your man page directories [1].

Tutorial

To illustrate the use of SAMtools, we will focus on using SAMtools within a complete workflow for next-generation sequence analysis. For simplicity, the tutorial uses a small set of simulated reads from E. coli. I have chosen E. coli because its genome is quite small — 4,649 kilobases, with 4,405 genes, and its entire genome fits into a single FASTA file of 4.8 megabytes. The sample read file is also small — just 790K — enabling you to download both within a few minutes.

If you are new to next-generation sequence analysis, you will soon find that one of the biggest obstacles is just finding and downloading sample data sets, and then downloading the very large reference genomes. By focusing on E. coli and simulated data sets, you can start small, learn the tool sets, and then advance to other organisms and larger sample data sets.

Overview

The workflow below is organized into six steps (see below):

Steps 3-6 are focused on the use of SAMtools. Steps 1-2 require the use of other tools. These initial steps do, however provide important context, and are therefore described below. That said, you are not required to actually perform any of steps yourself now, as intermediate files from these steps are available for download.

Generating Simulated Reads

First, we need a small set of sample read data. A number of tools, including ArtificialFastqGenerator, and SimSeq, will generate artificial or simulated sequence data for you. For this tutorial, I chose to use the wgsim tool (created by Heng Li, also the creator of SAMtools).

The command line usage for wgsim is:

wgsim [options] <in.ref.fa> <out.read1.fq> <out.read2.fq>

By default, wgsim reads in a reference genome in the FASTA format, and generates simulated paired-end reads in the FASTQ format.

If you specify the full E. coli genome, wgsim will generate simulated reads across the entire genome. However, for the tutorial, I chose to restrict the simulated reads to just the first 1,000 bases of the E. coli genome. To do so, I extracted the first 1K bases of the E. coli genome, placed these within a new file: NC_008253__1K.fna, and ran:

wgsim -N1000 -S1 genomes/NC_008253_1K.fna simulated_reads/sim_reads.fq /dev/null

Command line options are described below:

-N1000: directs wgsim to generate 1,000 simulated reads (default is set to: 1,000,000).-S1: specifies a seed for the wgsim random number generator; by specifying a seed value, one can reproducibly create the same set simulated reads./dev/null: wgswim requires that you specify two output files (one for each set of paired-end reads). However, if you set the second output to/dev/null, all data for the second set of reads will be discarded, and you can effectively generate single-end read data only.

wgsim will then output:

[wgsim] seed = 1

[wgsim_core] calculating the total length of the reference sequence...

[wgsim_core] 1 sequences, total length: 1000

gi|110640213|ref|NC_008253.1| 736 T G -

This indicates that wgsim has read in a reference sequence of 1K and has generated simulated reads to support exactly one artificial SNP, a T->G at position 736. By default, all artificial reads have a read length of 70, and the reads are written in the FASTQ format. For illustrative purposes, the first read is shown below:

@gi|110640213|ref|NC_008253.1|_418_952_1:0:0_1:0:0_0/1

CCAGGCAGTGGCAGGTGGCCACCGTCCTCTCTGCCCCCGCCAAAATCACCAACCATCTGGTAGCGATGAT

+

2222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222222

Note that in the FASTQ format, the first line specifies a unique sequence identifier (usually referred to as the QName), the second line specifies the sequence, and the fourth line specifies the Phred quality score for each base. wgsim does not generate artificial quality scores, and all bases are simply set to 2, indicating that the bases have a 0.01995 probability of being called incorrectly (for additional details, refer to Phred quality scores in the glossary.)

Aligning Reads

The next step is to align the artificial reads to the reference genome for E. coli. For this, I have chosen to use the widely used Bowtie2 aligner, from Johns Hopkins University. Again, you need not actually perform this step to use SAMtools, but it does provide important context, so I have included the details.

To align, use the command:

bowtie2 -x indexes/e_coli -U simulated_reads/sim_reads.fq -S alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sam

This directs bowtie to align the simulated reads against the e_coli reference genome, and to output the alignments in the SAM file format. Details regarding each command line option is provided below:

-

-x: the location of the reference genome index files. Bowtie requires that reference genome indexes be downloaded or built, prior to alignment. I have provided a pre-built index for e_coli on the github repository for this primer. -

-U: list of unpaired reads to align. -

-S: output alignments in the SAM format to the specified file.

For additional details on using bowtie2, refer to the online manual.

Understanding the SAM Format

As SAMtools is primarily concerned with manipulating SAM files, it is useful to take a moment to examine the sample SAM file generated by bowtie, and to dive into the details of the SAM file format itself. The first six lines from the bowtie SAM file are extracted below:

SAM files consist of two types of lines: headers and alignments. Headers begin with @, and provide meta-data regarding the entire alignment file. Alignments begin with any character except @, and describe a single alignment of a sequence read against the reference genome.

For now, we ignore the header-lines, auto-generated by bowtie, and focus instead on the alignments. Two factors are most important to note. First, each read in a FASTQ file may align to multiple regions within a reference genome, and an individual read can therefore result in multiple alignments. In the SAM format, each of these alignments is reported on a separate line. Second, each alignment has 11 mandatory fields, followed by a variable number of optional fields. Each of the fields is described in the table below:

| Field Name | Description | Example from the e_coli SAM file |

|---|---|---|

| QNAME | Unique identifier of the read; derived from the original FASTQ file. | gi|110640213|ref |NC_008253.1 |_418_952_1:0:0_1:0:0_0/1 |

| FLAG | A single integer value (e.g. 16), which encodes multiple elements of meta-data regarding a read and its alignment. Elements include: whether the read is one part of a paired-end read, whether the read aligns to the genome, and whether the read aligns to the forward or reverse strand of the genome. A useful online utility decodes a single SAM flag value into plain English. | 16: indicates that the read maps to the reverse strand of the genome. |

| RNAME | Reference genome identifier. For organisms with multiple chromosomes, the RNAME is usually the chromosome number; for example, in human, an RNAME of "chr3" indicates that the read aligns to chromosome 3. For organisms with a single chromosome, the RNAME refers to the unique identifier associated with the full genome; for example, in E. coli, the RNAME is set to: gi|110640213|ref|NC_008253.1|. | gi|110640213|ref|NC_008253.1| |

| POS | Left-most position within the reference genome where the alignment occurs. | 418 |

| MAPQ | Quality of the genome mapping. The MAPQ field uses a Phred-scaled probability value to indicate the probability that the mapping to the genome is incorrect. Higher values indicate increased confidence in the mapping. | 42: indicates low probability (6.31e-05) that the mapping is incorrect. |

| CIGAR | A compact string that (partially) summarizes the alignment of the raw sequence read to the reference genome. Three core abbreviations are used: M for alignment match; I for insertion; and D for Deletion. For example, a CIGAR string of 5M2I63M indicates that the first 5 base pairs of the read align to the reference, followed by 2 base pairs, which are unique to the read, and not in the reference genome, followed by an additional 63 base pairs of alignment. Note that the CIGAR string is a partial representation of the alignment because M indicates an alignment match, but this could indicate an exact sequence match or a mismatch [2]. If you would like to determine match v. mismatch, you can consult the optional MD field, detailed below. | 70M: 70 base pairs within the read match the reference genome. |

| RNEXT | Reference genome identifier where the mate pair aligns. Only applicable when processing paired-end sequencing data. For example, an alignment with RNAME of "chr3" and RNEXT of "chr4" indicates that the mate and its pair span two chromosomes, indicating a possible structural rearrangement. A value of * indicates that information is not available. | the E. coli simulated data is single read sequencing data, and all RNEXT values are therefore set to * (no information available). |

| PNEXT | Position with the reference genome, where the second mate pair aligns. As with RNEXT, this field is only applicable when processing paired-end sequencing data. A value of 0 indicates that information is not available. | the E. coli simulated data is single read sequencing data, and all RNEXT values are therefore set to 0 (no information available). |

| TLEN | Template Length. Only applicable for paired-end sequencing data, TLEN is the size of the original DNA or RNA fragment, determined by examining both of the paired-mates, and counting bases from the left-most aligned base to the right-most aligned base. A value of 0 indicates that TLEN information is not available. | the E. coli simulated data is single read sequencing data, and all RNEXT values are therefore set to 0 (no information available). |

| SEQ | the raw sequence, as originally defined in the FASTQ file. | CCAGGCAGTGGCAGGT... |

| QUAL | The Phred quality score for each base, as originally defined in the FASTQ file. | 222222222222222...: as noted above, wgsim does not generate artificial quality scores, and all bases are simply set to 2, indicating that the bases have a 0.01995 probability of being called incorrectly. |

Following the 11 mandatory fields, each alignment can also have a variable number of optional fields. For example, the bowtie generated SAM file for E. coli includes 8 additional fields for each alignment. Most of these are specific to bowtie, and are beyond the scope of this document [3]. However, two fields are part of the official SAM format, and are worth noting. These are detailed in the table below. Note that optional SAM fields always use the format: FIELD_NAME:DATA_TYPE:VALUE, where the DATA_TYPE of i indicates integer values and Z indicates string values [4].

| Field Name | Description | Examples from the e_coli SAM file |

|---|---|---|

| NM | The number of base pair changes required to change the aligned sequence to the reference sequence, known formally as the Edit Distance. |

NM:i:0 indicates a perfect match between the aligned sequence and the reference sequence. NM:i:1 indicates that the aligned sequence contain one mismatch. |

| MD | A string which summarizes the mismatch positions between the aligned read and the reference genome. | MD:Z:8G61 indicates a single base pair mismatch. Specifically, the aligned read matches the first 8 bases of the reference, after which it fails to match a G in the reference sequence, followed by 61 exact matches to the reference. |

Converting SAM to BAM

Now that you understand where alignments come from, know how to interpret SAM fields, and have a sample SAM file to play with, you are finally read to tackle SAMtools. As described above, our goal is to identify the set of genomic variants within the E. coli data set. To do so, our first step is to convert the SAM file to BAM. This is an important prerequisite, as all the downstream steps, including the identification of genomic variants and visualization of reads, require BAM as input.

To convert from SAM to BAM, use the SAMtools view command:

samtools view -b -S -o alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sam

-b: indicates that the output is BAM.-S: indicates that the input is SAM.-o: specifies the name of the output file.

BAM files are stored in a compressed, binary format, and cannot be viewed directly. However, you can use the same view command to display all alignments. For example, running:

samtools view alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam | more

will display all your reads in the unix more paginated style.

You can also use view to only display reads which match your specific filtering criteria. For example:

samtools view -f 4 alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam | more

-f INT: extracts only those reads which match the specified SAM flag. In this case, we filter for only those reads with flag value of 4 = read fails to map to the reference genome.

or:

samtools view -F 4 alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam | more

-F INT: removes reads which match the specified SAM flag.

You can also try out the -c option, which does not output the reads, but rather outputs the number of reads which match your criteria. For example:

samtools view -c -f 4 alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam

indicates that 34 of our artificial reads failed to align to the reference genome.

Finally, you can use the -q parameter to indicate a minimal quality mapping filter. For example:

samtools view -q 42 -c alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam

outputs the total number of aligned reads (819) that have a mapping quality score of 42 or higher.

Sorting and Indexing

The next step is to sort and index the BAM file. There are two options for sorting BAM files: by read name (-n), and by genomic location (default). As our goal is to call genomic variants, and this requires that we “pile-up” all matching reads within a specific genomic location, we sort by location:

samtools sort alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sorted

This reads the BAM file from alignments/sim_reads_aligned.bam and writes the sorted file to: alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sorted.bam.

Once you have sorted your BAM file, you can then index it. This enables tools, including SAMtools itself, and other genomic viewers to perform efficient random access on the BAM file, resulting in greatly improved performance. To do so, run:

samtools index alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sorted.bam

This reads in the sorted BAM file, and creates a BAM index file with the .bai extension: sim_reads_aligned.sorted.bam.bai. Note that if you attempt to index a BAM file which has not been sorted, you will receive an error and indexing will fail.

| A note about "Big Data" |

|---|

|

If you are already conversant with command line tools and possess basic programming skills,

you will quickly realize that there is nothing magical about next-generation sequence analysis.

You just need to learn the terms, the file formats, and the tools, and tie them all together.

However, there is one extra skill you will need to cultivate: patience. Once you move beyond

toy examples, and enter the world of real sequence data, all the concepts remain the same, but

all the files become much bigger, and everything takes longer -- usually a lot longer. For

example, sorting and indexing a single human exome BAM file can easily take 2-4 hours,

depending on read depth and your computer set-up. Worse, you may encounter an error after

two hours of processing, then make an adjustment, and wait another two hours to see if the

problem is fixed. It's a bit like rolling giant boulders up a mountain, having the

occasional one slip through, and starting all over from the beginning.

Many bioinformaticians hedge their patience by running next-generation sequencing pipelines on large distributed compute clusters, so that they can at least move dozens of boulders at once -- however, this is a topic for another primer. Until then, my best advice is to get the concepts right and start with small files. Then, pack your patience and work your way up to larger data sets. |

Identifying Genomic Variants

Now, we are ready to identify the genomic variants from our reads. Doing so requires two steps, and while one can easily pipe these two steps together, I have broken them out into two distinct steps below for improved clarity.

The first step is to use the SAMtools mpileup command to calculate the genotype likelihoods supported by the aligned reads in our sample:

samtools mpileup -g -f genomes/NC_008253.fna alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sorted.bam > variants/sim_variants.bcf

-g: directs SAMtools to output genotype likelihoods in the binary call format (BCF). This is a compressed binary format.-f: directs SAMtools to use the specified reference genome. A reference genome must be specified, and here we specify the reference genome for E. coli.

The mpileup command automatically scans every position supported by an aligned read, computes all the possible genotypes supported by these reads, and then computes the probability that each of these genotypes is truly present in our sample.

In our case, SAMtools scans the first 1000 bases in the E. coli genome, and then weighs the collective evidence of all reads to infer the true genotype. For example, position 42 (reference = G) has 24 reads with a G and two reads with a T (total read depth = 26). In this case, SAMtools concludes with high probability that the sample has a genotype of G, and that T reads are likely due to sequencing errors.

By contrast, position 736 (reference = T) has 2 reads with a C and 66 reads with a G (total read depth = 68). In this case, SAMtools concludes with high probability that the sample has a genotype of G. For each position assayed, SAMtools computes all the possible genotypes, and then outputs all the results in the binary call format (BCF).

The second step is to use bcftools:

bcftools call -c -v variants/sim_variants.bcf > variants/sim_variants.vcf

-c: directs bcftools to call SNPs.-v: directs bcftools to only output potential variants

The bcftools call command uses the genotype likelihoods generated from the previous step to call SNPs and indels, and outputs the all identified variants in the variant call format (VFC), the file format created for the 1000 Genomes Project, and now widely used to represent genomic variants.

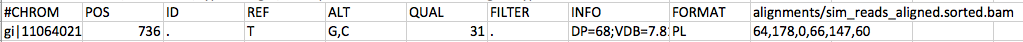

Understanding the VCF Format

If you take a peak at our newly generated sim_variants.vcf file, and scroll down to the first line not starting with a # symbol, you will see our lone single nucleotide variant (SNV). And, if all has gone well, it should match the SNV at position 736 output by wgsim way back in Step 1! Congratulations!

Of course, to truly understand the variants identified in your sample, you must take a slight detour and understand the basics of the Variant Call Format (VCF). We will not cover all the details here, but just enough to give you a basic understanding.

First, just like SAM files, VCF files contain header lines, which begin with # or ## symbols, and data lines, which do not begin with a # symbol. The header contains important information, such as the name of the program which generated the file, the VCF format version number, the reference genome name, and information regarding individual columns within the file.

Each data line is required to have eight mandatory columns, including CHROM reference, POSition within the chromosome, REFerence sequence, and ALT sequence. Directly after these eight is a FORMAT column used to describe the format for all subsequent sample columns. VCF can contain information regarding multiple samples, and each sample gets its own column.

Within our VCF file, the FORMAT column is set to “PL”. If you search within the header, you can find that PL is defined as:

##FORMAT=<ID=PL,Number=G,Type=Integer,Description="List of Phred-scaled genotype likelihoods">

These are the same genotype likelihoods described above in step 5.

With this knowledge in hand, let’s try to decipher the lone SNV we have identified:

According to the data columns, the SNV was identified in E. coli at position 736, where the reference is T, and our sequencing data supports two possible alternative sequences: G and C. INFO DP=68 indicates that the position has a read depth of 68, and the FORMAT column indicates that all samples (in this case, just our one) will include a list of genotype likelihoods. In our case, this results in the cryptic string: “64,178,0,66,147,60”.

Based on the reference and the alternative sequences, SAMtools automatically calculates the following genotypes, in this exact order [5][6]:

| Genotype | Phred Scaled Score | Likelihood p-value |

|---|---|---|

| TT | 64 | 3.981-07 |

| TG | 178 | 2.512e-18 |

| GG | 0 | 1.0 |

| TC | 66 | 2.512e-07 |

| GC | 147 | 1.995e-15 |

| CC | 60 | 1.000e-06 |

This indicates that the GG genotype is very likely the true genotype in your sample. The reads in our sample therefore support a Single Nucleotide Variant (SNV) from T to G at position 736.

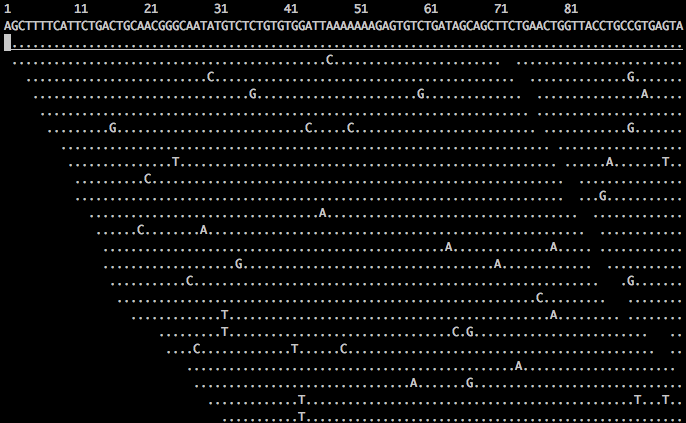

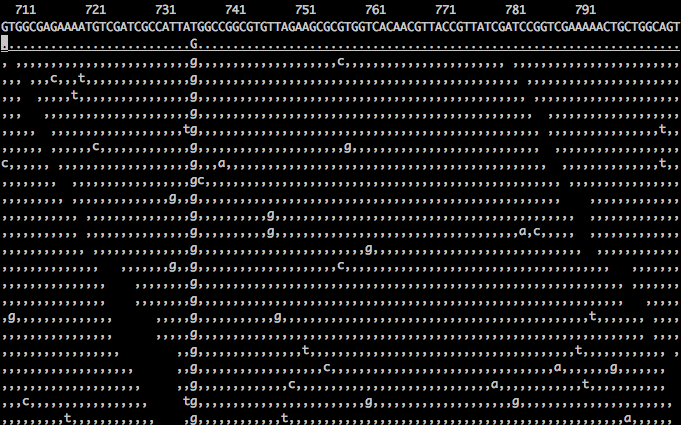

Visualizing Reads

For the final step, we will use the SAMtools tview command to view our simulated reads and visually compare them to the E. coli reference genome. To do so, run:

samtools tview alignments/sim_reads_aligned.sorted.bam genomes/NC_008253.fna

You will see a screen, such as the one shown below.

In this view, the first line shows the genome coordinates, the second line shows the reference sequence, and the third line shows the consensus sequence determined from the aligned reads. Throughout tview, a . indicates a match to the reference genome.

You can toggle a mini help screen by pressing the ? key, and from here determine the main keys for navigating across your reads. For example, you can use the h,j,k,l keys (or the cursor keys) to make small movements. For now, let’s zero in on our identified variant at position 736. To do so, press the space bar a few times until you reach position 730. Here you can see that the consensus call is a G v. reference of T, and you can scroll through all the aligned reads by pressing the down cursor key (sample screenshot shown below).

| Gotcha: Goto a specific location. |

|---|

| Within tview you can press g to go to a specific genomic location. However, if you type g and enter a position, such as 736, nothing will happen. This is because the location must be specified in the form: RNAME:position, e.g. for human data, you would type: chr3:200000. In our case, the RNAME is set to the identifier associated with the full genome, which is: gi|110640213|ref|NC_008253.1|. Therefore, to jump to position 736, you would have to enter the rather long string: gi|110640213|ref|NC_008253.1|:736. |

Further Reading

Hopefully, this primer has helped you take your first steps into the world of SAMtools and next-generation sequence analysis. To continue on, I recommend the following resources:

-

Bowtie2 Home, and Online Manual.

-

Cock PJ et al. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 Apr;38(6) [PubMed]

-

Danecek P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011 Aug 1;27(15):2156-8. [PubMed].

-

Li H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009 Aug 15;25(16):2078-9. [PubMed]

-

The SAM Format Specification [PDF].

-

wgsim repository on github.

Footnotes

[1] If you are uncertain where to copy the SAMtools man page, or are uncertain where your existing man pages are located, try typing:

man -w

this will display the current set of man paths. samtools.1 is considered a “section 1” man page, reserved for user commands. You therefore need to copy it into a directory named man1. For example, on my system, I copied samtools.1 to: /usr/local/share/man/man1/.

[2] The ambiguous nature of M within the CIGAR string has caused some confusion within the community, and biostars.org has an interesting thread on whether the CIGAR format itself should be redefined.

[3] If you are curious, you can look up all the bowtie specific SAM fields in bowtie2 manual (refer to “optional fields” within the SAM output section.)

[4] The complete list of data types and predefined optional fields are provided in the official SAM Format Specification.

[5] How exactly is the order of genotypes determined? This is formally specified in the VCF version 4.1 specification. According to the specification, each allele is assigned an index value, starting at 0. For example, in a VCF row with reference T and alternative alleles G and C, we set T=0, G=1, and C=2.

With three alleles, and the assumption that we are working with a diploid organism, there are (3 choose 2 or P(3,2)) permutations for a total of 6 permutations. Each permutation is described by their index values. For example, TT (both alleles are T) is described as (0,0), whereas CC (both alleles are C) is described as (2,2). The ordering of each permutations is then determined by the equation: F(j,k) = (k*(k+1)/2)+j, where j,k refer to allele index values. For example, TT (0,0) = 0, whereas CC (2,2) = (2*(2+1)/2) + 2 = 5.

[6] But, wait! The E. coli genome is haploid, i.e. there is only a single set of genes. And, there is therefore never the possibility of having two alleles at the same position. SAMtools, however is designed to work with diploid genomes, and always calculates genotypes based on the assumption of a diploid genome. To get around this assumption in our simulated case, we can assume that the E. coli reads come from a pool of samples, and the genotypes represent alternatives alleles present in the pool.

Glossary

alignment: the mapping of a raw sequence read to a location within a reference genome. The mapping occurs because the sequences within the raw read match or align to sequences within the reference genome. Alignment information is stored in the SAM or BAM file formats.

bcftools: a set of companion tools, currently bundled with SAMtools, for identifying and filtering genomics variants.

bowtie: widely used, open source alignment software for aligning raw sequence reads to a reference genome.

BAM Format: binary, compressed format for storing SAM data.

BCF Format: Binary call format. Binary, compressed format for storing VCF data.

CIGAR String: Compact Idiosyncratic Gapped Alignment Report. A compact string that (partially) summarizes the alignment of a raw sequence read to the reference genome. Three core abbreviations are used: M for alignment match; I for insertion; and D for Deletion. For example, a CIGAR string of 5M2I63M indicates that the first 5 base pairs of the read align to the reference, followed by 2 base pairs, which are unique to the read, and not in the reference genome, followed by an additional 63 base pairs of alignment.

FASTA Format: text format for storing raw sequence data. For example, the FASTA file at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_008253 contains entire genome for Escherichia coli 536.

FASTQ Format: text format for storing raw sequence data along with quality scores for each base; usually generated by sequencing machines.

genotype likelihood: the probability that a specific genotype is present in the sample of interest. Genotype likelihoods are usually expressed as a Phred-scaled probability, where P = 10 ^ (-Q/10). For example, if the genotype TT (both alleles are T) at position 1,299,132 in human chromosome 12 (reference G) is 37, this translates to a probability of 10^(-37/10) = 0.0001995, meaning that there is very low probability that the reads in your sample support a TT genotype. On the other hand, a genotype of AA at the same position with a score of 0 translates into a probability of 10^(-0) = 1, indicating extremely high probability that your sample contains a homozygous mutation of G to A.

mate-pair: in paired-end sequencing, both ends of a single DNA or RNA fragment are sequenced, but the intermediate region is not. The two ends which are sequenced form a pair, and are frequently referred to as mate-pairs.

QNAME: unique identifier of a raw sequence read (also known as the Query Name). Used in FASTQ and SAM files.

paired-end sequencing: sequencing process where both ends of a single DNA or RNA fragment are sequenced, but the intermediate region is not. Particularly useful for identifying structural rearrangements, including gene fusions.

Phred-scaled probability: a scaled value (Q) used to compactly summarize a probability, where P = 10^(-Q/10). For example, a Phred Q score of 10 translates to probability (P) = 10^(-10/10) = 0.1. Phred-scaled probabilities are common in next-generation sequencing, and are used to represent multiple types of quality metrics, including quality of base calls, quality of mappings, and probabilities associated with specific genotypes. The name Phred refers to the original Phred base-calling software, which first used and developed the scale.

Phred quality score: a score assigned to each base within a sequence, quantifying the probability that the base was called incorrectly. Scores use a Phred-scaled probability metric. For example, a Phred Q score of 10 translates to P=10^(-10/10) = 0.1, indicating that the base has a 0.1 probability of being incorrect. Higher Phred score correspond to higher accuracy. In the FASTQ format, Phred scores are represented as single ASCII letters. For details on translating between Phred scores and ASCII values, refer to Table 1 of this useful blog post from Damian Gregory Allis.

read-length: the number of base pairs that are sequenced in an individual sequence read.

read-depth: the number of sequence reads that pile up at the same genomic location. For example, 30X read-depth coverage indicates that the genomic location is covered by 30 independent sequencing reads. Increased read-depth translates into higher confidence for calling genomic variants.

RNAME: reference genome identifier (also known as the Reference Name). Within a SAM formatted file, the RNAME identifies the reference genome where the raw read aligns.

SAM Flag: a single integer value (e.g. 16), which encodes multiple elements of meta-data regarding a read and its alignment. Elements include: whether the read is one part of a paired-end read, whether the read aligns to the genome, and whether the read aligns to the forward or reverse strand of the genome. A useful online utility decodes a single SAM flag value into plain English.

SAM Format: Text file format for storing sequence alignments against a reference genome. See also BAM Format.

SAMtools: widely used, open source command line tool for manipulating SAM/BAM files. Includes options for converting, sorting, indexing and viewing SAM/BAM files. The SAMtools distribution also includes bcftools, a set of command line tools for identifying and filtering genomics variants. Created by Heng Li, currently of the Broad Institute.

single-read sequencing: sequencing process where only one end of a DNA or RNA fragment is sequenced. Contrast with paired-end sequencing.

VCF Format: Variant call format. Text file format for storing genomic variants, including single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, deletions and structural rearrangements. See also BCF format.

License

SAMtools: A Primer, by Ethan Cerami is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.